As I rummaged through my Twitter/X account to remove older posts, I stumbled on a thread I thought was worthy of a short article. It concerns how police forces score individuals for targeted action where violence is concerned. The thread was specifically in response to the criticism faced by the Metropolitan Police’s use of what was more widely known as the Gangs Matrix back in 2022.

The ‘Gangs Violence Matrix’ (hereafter GVM) was introduced in 2012 as part of the Trident Gang Crime Command rebrand. In a nutshell, it was a list of individuals referred to as ‘gang nominals’ (persons of interest to police for involvement or risk of gang violence) who had been scored using a combination of crime incident and intelligence submission data and graded in a way that denoted their level of risk and or harm. The outputs could be used to aid police resource decisions.

Full details on the Gangs Violence Matrix can be found here (link active as of 2024–10–09). The GVM was discontinued in February 2024.

Offender matrices

Most similar tools designed to forecast risk focus on recidivism. Uniquely the GVM was designed to provide a forecast of the prospective risk of individuals who are in the community (i.e. not in custody/prison, and in most cases individuals who have no rehabilitative or criminal justice supervision requirements).

Such forecasts have been made for many years for domestic abuse (i.e. Strathclyde Police, now Police Scotland, Recency Frequency Gravity score), but less frequently for non-domestic violence. Evidence and research on exactly how to fulfil the need to prioritise individuals for non-domestic violence (in line with ALGOCARE principles where UK policing is concerned) are limited. We have seen examples using firearms violence in the United States, and there is some recent research with regard to knife and most serious violence in the United Kingdom.

The UK research includes knife-carrying — see Iain Brennan work on Weapon-carrying and the reduction of violent harm) and most serious violence — see National Data Analytics Solution/NDAS and West Midlands Police work to forecast those at risk of most serious violence offending.

Generally, we see from police and health violence data in the UK that non-domestic serious violence is concentrated:

- among young men,

- in more deprived urban neighbourhoods,

- in the presence of others,

- under the influence of alcohol,

- or where weapon carrying and low trust in police exists.

Prior offending, peer relationships and involvement in criminal illicit activity additionally can enhance the risks of violent offending. These are the kinds of variables that are often tested in forecast models for individual persons.

A criticism of the GVM was that it didn’t score all individuals involved in non-domestic violence with these characteristics or variables. To be ‘matrixed’ for prioritisation could be more subjective. For example, you just need two or more qualifying agencies to label you as a ‘gang member’. So, there were ethical problems with the criteria.

I don’t intend to go into those ethical issues, there is considerable material in the public domain already on this point. I will say, if you were assessing the GVM against the ALGOCARE principles, there are certainly aspects of the GVM that were not challengeable, responsible and explainable, which continued to be criticised until it was discontinued.

Confidence in machine learning models

One issue that seems to drive mistrust, scepticism or challenge to use of matrices in policing is wider misunderstanding about how they work. There continues to be considerable caution towards ‘machine learning models’ where they are used in policing to make decisions regarding individuals. I think this can be partly driven by the inaccessible language used when technical persons talk about them.

Instead of saying Machine Learning Models and Predictive Algorithms, we might help our cause using plain English for non technical audiences. For example, “models are attempts at using some things we know about, to determine something we don’t know about”.

And use relatable examples. For anyone who has ever applied for a credit card, loan or mortgage — your financial and socio-demographic/economic information would have been scored to test for suitability (using things that are known such as age, home ownership, outgoings, marital status), and a decision made as to whether you will be granted the card/loan or not (predicting an unknown, whether you will be able to maintain payments without defaulting).

Aside from mistrust, the other key question we need to highlight - are data driven approaches better than humans? Rarely does equal attention fall on the question of whether models are better than allowing individuals to make their own decisions. So perhaps we have more trust in human practitioners and experts to make correct decisions?

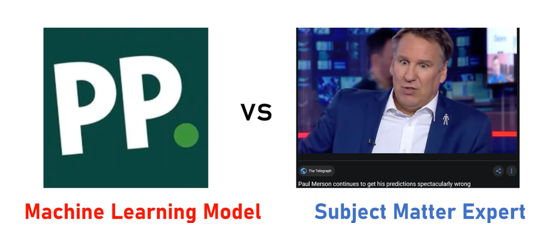

Using another relatable example, let us try to understand the difference between a model and a human in the following example.

Think of Paddy Power as a machine model. They create fixed betting odds using the information on every individual player, game, touch, goal, assist and so on. They use all relevant (and perhaps seemingly irrelevant) data available to determine the odds. There is little room for error because of the costs involved.

Now think of a football pundit as a Subject Matter Expert (SME). Typically, they draw on a much smaller sample of experience. No two SMEs are the same. There is a huge variation in their knowledge, experience and in how they apply decision-making, and that applies to policing, and practitioners as it does with any profession.

Different people when presented with the same situation and information will make different decisions and judgements based on their own individual experiences. Paul Merson might have an Arsenal bias when he predicts where they will finish in the league.

Models whilst they can be more objective and apply rules with consistency are also imperfect. But, I would argue that practitioners who have access to data-informed products can use them to augment better decision-making than clinical assessment alone so long as they understand what it is they (models) are doing. And they must be done with ethics and transparency in mind.

Where do you place importance in making your betting decision? Odds formed by models or your favourite TV pundits? Probably both right, along with your own instincts and bias? And apologies to non-sports fans if this analogy makes no sense.

Today the Metropolitan Police has moved towards a new resource known as the ‘Violence Harm Assessment’.

What is the alternative?

Without data driven prioritisation tools, practitioners and frontline professionals are still going to need to make decisions about whom they target finite resources. We can change, challenge, develop and understand the processes in a model, but doing this for decisions made in the minds of many practitioners is much more difficult.

Both data and human methods should be considered in decision-making processes.

Resources

Below are some studies that deal with individual forecasts and person prioritisation in policing and criminal justice

I originally posted this on Medium